- This event has passed.

Something BIG!

Sponsored by the Ernest and Joan Trefz Foundation

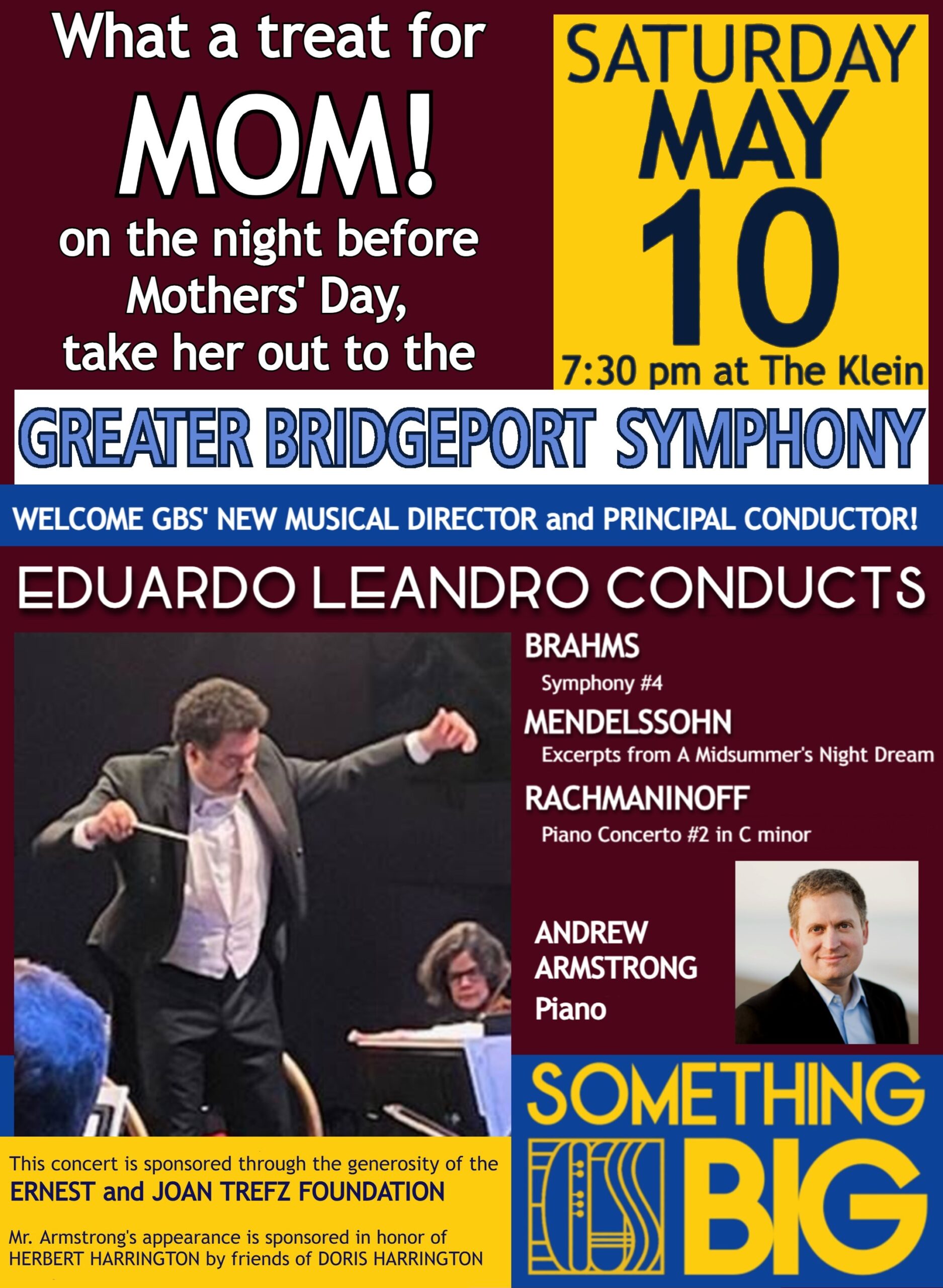

This is it! Maestro Eduardo Leandro’s grand inaugural concert as GBS’ new Music Director and Principal Conductor! We’ve promised an amazing night of music and the concert on May 10 will live up to the show’s name, Something Big! Pianist Andrew Armstrong, a perennial favorite of GBS who got his professional start here some 20+ years ago, will play Rachmaninoff’s “Piano Concerto No. 2,” and the orchestra will also render Mendelssohn’s “Midsummer Night’s Dream” overture and Brahms’ “Symphony No. 4. “. “I want to present music that the audience will really enjoy, and that the orchestra will love to play,” Maestro Eduardo said.

This concert is on the eve of Mother’s Day. What a great way to spend the night out with family!

“Something Big” honors the late Fairfield philanthropists Herbert F. Harrington Jr., founder of Rotair Aerospace Corp., and wife, Doris Demonkos Harrington, former vice president of Rotair, who for many years served as GBS president and board chairwoman. Both, in their 90s, passed away recently. Pianist Andrew Armstrong was a long-time friend of the Harringtons. His appearance is being offered in honor of “Herb,” and supported by friends of his wife.

Andrew Armstrong, Piano

Praised by critics for his passionate expression and dazzling technique, pianist Andrew Armstrong has delighted audiences across Asia, Europe, Latin America, Canada, and the United States, including performances at Alice Tully Hall, Carnegie Hall, the Kennedy Center, London’s Wigmore Hall, the Grand Hall of the Moscow Conservatory, and Warsaw’s National Philharmonic.

This season, all kids under 19 years old will be admitted FREE when accompanied by an adult; accompanying adults will get 15% off their single ticket prices. Please note that our concerts will begin one half hour earlier this season, at 7:30 PM.

Pre-Concert Talk presented by Russell Fisher

University of Bridgeport, Associate Chair – Music Department, Assistant Professor of Music

6:30 PM

PROGRAM NOTES:

Felix Mendelssohn (1809 -1847)

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Overture

Mendelssohn’s music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream was written in two parts. The overture dates from 1826 when he was seventeen years old. It was inspired by a translation of the play into German, and was intended as a concert piece rather than as incidental music. It is generally regarded as one of Mendelssohn’s finest works for the brilliance of his orchestration and scene painting. It follows the classical sonata form used extensively by Haydn Mozart and Beethoven, with the main sections punctuated by four chords on the woodwinds, heard at the outset. The music describes the fairies, the grandeur of the court of Thesius, the four lovers and the rustics including the braying of Bottom with the asses head. It was premièred in Szczecin on 20 February 1827. This was Mendelssohn’s first appearance at a public concert and he had to travel eighty miles through a snowstorm to get it. In the same concert he appeared as soloist, playing one of the pianos in his own Concerto in A-flat major for 2 pianos, followed by Weber’s Konzertstück in F minor. To demonstrate his versatility further he joined the first violins for the last work of the concert: Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

– Duncan Gilles

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 -1943)

Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, op. 18

Moderato

Adagio sostenuto

Allegro scherzando

Andrew Armstrong, Piano

The gaunt 24-year-old Sergei Rachmaninoff lies on a couch, repeating a mantra: “You will begin to write your concerto. You will work with the greatest of ease. The concerto will be of excellent quality.”

Rewind three years, to the chaotic premiere of Rachmaninoff’s First Symphony. The orchestra was scrappy, the conductor drunk, the critics savage. Rachmaninoff felt “a paralyzing apathy. Half my days were spent on a couch, sighing over my ruined life.” Today, he might be diagnosed with clinical depression. Rachmaninoff wrote nothing for three years, but continued to tour as a concert pianist. After a successful London performance, he found himself promising a new piano concerto. “A second and better one.”

Rachmaninoff wasn’t confident he could deliver. Friends recommended a psychiatrist who specialized in hypnotherapy and the repetition of positive mantras. Rachmaninoff responded well to these sessions, and was able to move forward with the new work.

The Second Piano Concerto breathes with the air of Rachmaninoff’s childhood. The concerto opens with evocations of the deep bells of the orthodox church. The orchestra answers with a slow, step-wise chant melody.

In the slow movement we might feel the cooling breeze of Rachmaninoff’s beloved family residence, Ivanovka. “This steppe was like an infinite sea where the waters are actually boundless fields of wheat, rye, oats, stretching from horizon to horizon.”

At Ivanovka, he found happiness, motivation. “The smell of the Earth, mowed rows and blossoms. I could work—and work hard. Every Russian feels strong ties to the soil. Perhaps it comes from an instinctive need for solitude.”

The finale, despite its minor mode, brims with the crackle of electricity. The premiere of this concerto ushered in Rachmaninoff’s most productive period. In the next fifteen years, he would write many of his most beloved works.

– Tim Munro

Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897)

Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98

Although his catalog lists just four symphonies, Brahms wrote several other works that come close to that genre: his First Piano Concerto was indeed planned as a symphony, and the Second (which is in four movements) has been called a symphony with piano obbligato. Although the Second and Third Symphonies were introduced in Vienna, Brahms decided to give his Fourth Symphony an out-of-town tryout. He himself conducted the premiere (in October 1885) with the Meiningen Court Orchestra, where the audience was enthusiastic. Vienna was not so receptive when the work was introduced there a few months later. As it turned out, a mere ten years after his First Symphony had been given its premiere, Brahms had written his last symphony. Two years later came the Double Concerto, whose two solo parts (violin and cello) remind us of the old sinfonia concertante form, but there were to be no more symphonies.

For his final essay in symphonic form, Brahms produced a monumental work whose first movement grows from the simplest of materials, a simple rising and falling interval, out of which he develops long lines of powerfully emotional, yet unsentimental grandeur. The relentless organic development, which begins even as themes are being stated, leads to a complex interaction of motives and melodic fragments. The composer’s friend Elisabeth von Herzogenberg wrote to him of her fears that he was dwelling too much on creating intricate thematic connections that would obscure his musical communication for the untrained listener: “…one rejoices with all the excitement of an explorer or scientist on discovering the secrets of your creation! But there comes a point where a certain doubt creeps in…that its beauties are not accessible to every normal music-lover.”

What makes the music so compelling, in fact, may be the way the longer lines ebb and flow with great urgency and lyrical beauty, while at the same time the contrapuntal complexities lend substance and richness to the texture. As an example of how the opposing camps of Wagnerites and Brahmsians always seemed to have something nasty to say about each other, note the comment of composer Hugo Wolf – one of the Symphony’s detractors – that Brahms was “composing without ideas.” Schoenberg, although he followed in the wake of Wagner’s progressive chromatic proclivities, was a strong supporter of what he described as Brahms’ technique of “developing variation.” Certainly Beethoven had proved that minimal materials could be the source of substantial music.

After the powerful conclusion of the first movement, Brahms introduces the second movement with a forceful statement by two horns, followed by a ravishing passage in which all of the strings play delicate pizzicato chords supporting a sustained melody in the winds. As in the famous finale (in which Brahms looks to earlier musical models for his structure), there is an archaic quality to this music, which is the result, in part, of the composer’s use of the medieval Phrygian mode. This rather mournful meditation is interrupted by more animated passages, but there is an overriding tone of “the shadow of an inevitable fate.” (Karl Geiringer)

In the other Brahms symphonies, there is no movement that could be said to fulfill the role of the scherzo in the Beethoven mold; that is not true in the Fourth Symphony. Here the third movement overflows with high spirits and raw energy, with the piccolo and triangle added to the performing forces for extra sizzle. The structure, though, is not that of a traditional scherzo with a contrasting middle section; in fact, this movement is in sonata form, and it includes material that prompted Hermann Kretschmar (writing in 1887) to note “its hastening, restless rhythms…its suddenly pulsing energy, and…the predominant harshness of its character.”

Brahms, a diligent student of musical history, was always ready to draw on the styles and forms of earlier ages. The final movement of the Fourth Symphony is the best-known such instance, and it is usually characterized as a passacaglia, with reference to Bach. Although the theme which recurs throughout is drawn from Bach’s Cantata No. 150, conductor and Baroque specialist Nikolaus Harnoncourt feels strongly that the form itself is more typical of the concluding movements in French operas from the Baroque era (especially Rameau). What is undeniable is the sense of cumulative power Brahms creates with his “old-fashioned” methods. The theme is repeated some 30 times, but the musical material is organized (texturally, dynamically, and above all emotionally) into a sonata-like structure: The extended opening section is followed by more relaxed (but still troubled) passages of a lyrical, yearning character (in which a solo flute is prominently featured). A renewed energy marks the beginning of a kind of development, culminating in three variations that recall the opening ones. The concluding pages of the Symphony are relentlessly charged with defiance and bristling with slashing intensity. For once, there is no coda. No triumph, no joy, no radiant string chords. The rest… is silence.

— Dennis Bade